Pretty often, I get questions by phone and e-mail from people who are just getting started with their digital preservation projects, and need to scan photos or documents. Almost always, they seek advice about what kind of scanner to buy. A lot of times, the questions are similar:

I this article, I hope to lay down some basic recommendations to get beginners looking for a scanner that suits their needs.

The first step: consider the size of the task

For most people at home, and even some institutions with objects to scan, the vast majority of documents ripe for scanning will physically fit in a letter-sized, flatbed scanner (such as the one pictured at the top of this article). For these types of collections, the vast majority of scanners out there will be just fine for your needs. However, there are people who have larger objects: photos and maps as large as 11 inches by 17 inches, or perhaps even bigger. And then there are the smaller items and specialty objects: photographic negatives, slides, and contact sheets.

And so, the first step should begin before you even buy the equipment: take stock of your archives and find out if they have any specific needs. Consider how much of your collection are large items, and how much of it consists of very small objects, transparencies, film and negatives.

If your large items comprise only a small amount of your total items (say, 10-15% or less) and you don’t see yourself acquiring more in the near future, then you might get away with a standard-sized scanner, and outsourcing the digitization of these large objects to a third party. Some local print shops, and even national chains like Alphagraphics and Fedex Office provide these services for a fee, or can refer you to a vendor. Additionally, our own facility at Rutgers provides a similar service to the public for a nominal fee, based on availability.

If removing these objects to an outside location is out of the question, if the amount of oversized objects you’re scanning is large, or you plan on digitizing oversized objects regularly, then it may be wiser to invest in a specialty scanner that handles these objects. You’ll also want to look for transparency and film support in any scanner, if your collection contains these types of objects. I’ll list a couple of examples in a bit.

The second step: consider the capabilities of what you want to buy

For most applications, you really won’t need to spend a whole lot of money to get a good scanner. However, getting something excruciatingly cheap can come with a price. A happy medium needs to be found between these two competing factors.

I’ve developed a set imaging standards that set minimum resolutions for scanning photographs and documents. 600 dpi is a minimum we commonly aim for, and you’ll find that even the cheapest of modern flatbed scanners can meet this requirement. Even so, I’m recommending to most buyers that they look into scanning equipment that optically scan at least at resolutions of at least 4800dpi.

Why is this? Mainly because while 600dpi is just perfect for things that are 4 x 6 inches and larger, you will need to scan at much higher resolutions for things like wallet sized photos, small postcards, and especially those slides and film negatives. Such small items pack a large amount of detail in a tiny space, and a lot of that gets lost when you just assume everything will be okay when scanned at 600 dpi.

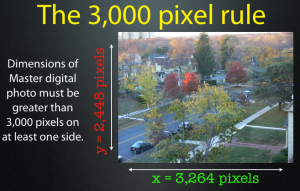

The main caveat I’ve placed in my standards documentation is the 3,000 pixel rule: the idea that in order to get a decent amount of detail out of any object, at least one side of the image must be at least 3,000 pixels long or wide. For small 35mm slides or even 3 x 5 inch photo prints, 600 dpi just isn’t high enough resolution to meet this goal. And so, higher resolution settings have to be used to capture the necessary detail. It’s not uncommon for us at the SCC to scan slides as high as 3200 dpi to get an effective, detailed scan.

The good news is that most scanners are very reasonably priced and yet deliver excellent features and high scanning resolutions. It’s possible to get a good, current, letter sized scanner with adequate film and transparency capability for under $100 each. Unfortunately, larger flatbed scanners (mostly the 11 x 17 inch variety) are more of a niche market, and can be expensive. Expect to pay between $1,000 and $5,000 for such devices, and solutions for bigger items might be even higher.

One other thing to keep in mind: if your collection is largely consisting of three dimensional artifacts, or even really large two-dimensional maps (12 by 14 inches or wider) then a flatbed scanner is not what you’re going to need for visual imaging of these kinds of objects. You will definitely need to invest in a different solution, such as a good digital camera and possibly an appropriate imaging platform, or look into outsourcing this work to a capable third party. I’ll do up a writeup of some of these options in an upcoming blog post.

Making your decision

Once you have the needed requirements and criteria down, it’s time to do some shopping. There are multiple online vendors out there, and they all have a wide array of different scanning equipment you can buy. Fortunately, most have the capability to narrow down the available selections based on what your looking for. If you have a preference for a specific brand, or want to just limit to larger flatbeds and higher resolutions, most vnedors will let you comaprison shop based on your choices.

Once you have a few candidate models in mind, it’s a good idea do a little Googling and asking colleagues for their opinions before you commit to buying. Make sure the scanner you’re looking to buy has a good track record, and that users aren’t having frequent reliability or compatibility problems. Some sites, such as imaging-resource.com and test freaks, provide detailed write-ups of each model they test, and even provide test scans and comparisons.

What we use

This past summer, the Scholarly Communication Center (the facility where I work) began refurbishing a public computer lab into what we will soon open as a Digital Curation Research Center. This lab is being outfitted with hardware to tackle a number of different digital curation tasks, and among those pieces of hardware is a set of flatbed scanners for digitizing documents and photos. After consideration of our needs, purchasing a few models from different vendors, and sending quite a few of them back for being sub-ar to our requirements, we settled on a couple of different models.

(Please note: this isn’t an endorsement of any specific scanning vendor. Your needs may be different, and could require you to purchase something different from the choices made here).

Standard, letter-size scanner: The majority of our flatbed scanning work will be done on EPSON Perfection V300 flatbed scanners. They are capable of imaging at 4800 x 9600 dpi, have built-in film and slide scanners, support Mac and Windows systems, and have this unique horizontal hinge that allos the top cover to lift to the side in a way that can support brittle books really well. All for under $90 apiece.

support Mac and Windows systems, and have this unique horizontal hinge that allos the top cover to lift to the side in a way that can support brittle books really well. All for under $90 apiece.

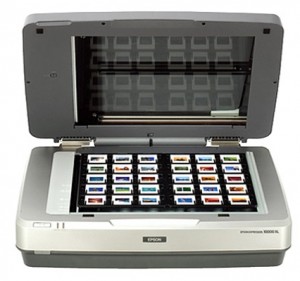

Plus-size/bulk transparency flatbed scanners (2): The lab has two tabloid-size scanning workstations: one Microtek Scanmaker 1000XL Pro we had purchased from a Previous project, and anEPSON 10000XL Photo scanner. The Microtek scanner is a workhorse and provides excellent imagery, but unfortunately is no longer for sale in the United States now that the company has exited the retail market. The Epson model, however, is a worthy successor, and provides excellent tabloid support in addition to some batch-slide scanning capabilities. In some of our slide-scanning projects, we’ve been able to arrange up to 30 slides at a time and have this scanner produce individual, 3200 dpi scans of each frame, completing each set in about an hour.

What about All-in-One printers/scanners/faxes?

The All-In-One solution is a tempting proposition for some very small outfits and home users. In fact, a lot of printer and scanner manufacturers like HP, Canon, Kodak and EPSON fill their product lineups with these combo devices. They’re beneficial for users who have occasional light scanning and printing needs, and provide repeat business for the vendors, who can sell these devices at a loss knowing that users will have to come back later for ink and supplies.

These solutions will make sense for home users who have boxes of photos and documents in their attics and closets, and want to preserve these items in a digital form while clearing out some space. I fact, use an HP Photosmart C4000 series printer/scanner combo in my home, and am quite happy with it. However, I wouldn’t recommend such items for regular business or institutional use. Bear in mind that just like any other combo device, you may find yourself having to toss a perfectly good scanner if the printer portion happens to malfunction, or vice versa. In my experience, printers and scanners get a lot more mileage in a business or institutional setting, and these units are just not built to withstand the sheer volumes that might be required of them in that environment.