On July 7, Sony announced that production of MiniDisc playback equipment would cease in September of 2011. According to Sony, the format’s creator, the blank MiniDisc recording media will continue to be manufactured for up a year beyond the players’ discontinuation.

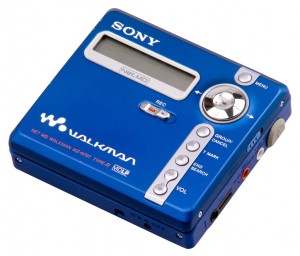

MiniDisc never made as big a splash as Sony had hoped, at least in markets outside of Asia. Introduced in 1992, Sony had envisioned that the format would be just as ubiquitous in the 1990s as the audio cassette – and another Sony invention, the Walkman – was in the 1980s. Unlike Audio CDs, MiniDiscs offered a more compact design to increase portability, greater durability and anti-skip capabilities, and all MiniDisc playback equipment was capable of writing to recordable and re-writeable media from the outset. By contrast, the first sub-$10,000 CD writers wouldn’t become available until 13 years after Compact Disc’s 1982 introduction to the market, and almost 3 years after MiniDisc was widely available.

Unfortunately, MiniDisc had barriers to adoption from the outset, most of which were placed – deliberately or otherwise – by the company who introduced the format in the first place.

The ’90s marked an era where audio vendors knew there was a growing appetite for improved, portable digital playback, but couldn’t agree on a single platform. Consequently, the market was flush with differing standards, and MiniDisc had to find a place in an environment already crowded with other options vying to be the successor to analog cassettes. Sony never really made an effort to rationalize this, and ignoring past lessons, such as the Beta-vs-VHS wars of the video world, instead seemed to think that this was a perfectly sustainable situation. From Sony’s initial press release announcing MiniDisc:

“The announcement of this important new technology for personal listening supports our view that no single audio format can meet every consumer’s needs,” noted Ron Sommer, president and COO, Sony Corporation of America. “We do not see MD displacing any current formats. Instead, we expect it to co-exist with CD, DAT and other cassette formats, each of which meets specific consumer requirements.”

There were also limitations imposed which dampened consumer interest. MiniDisc used ATRAC audio compression; a proprietary, lossy format which degraded the quality of the audio enough to cause most audiophiles to criticize the medium. And even less-discerning consumers found that while MiniDisc seemed to be a competent digital format, digital duplication was hobbled by a Digital Rights Management scheme known as SCMS, severely limiting one of the format’s most attractive features. Even worse, although the format was licensed to other audio equipment makers, MiniDisc was largely a Sony venture, with little interoperability. But the largest inhibitor to its adoption was price: in North America, 1992-era MiniDisc models sold for between $800 and $1,000; out of reach for many casual listeners, and mostly only affordable by those same affluent, dedicated audiophiles who found its compression methods unattractive.

While it never really caught on in mass markets outside of Asia, MiniDisc did find a niche in some broadcast and studio operations. By the mid to late ’90s, the price of the recorders and discs dropped enough that smaller, independent artists and musicians found it to be a reasonably good digital recording medium. The small size of portable recorders also made it a useful tool for journalists in the field, being both more durable and providing recordings of better quality than most tape recorders. And smaller radio and broadcast outfits – particularly college radio stations – used MiniDisc as a slightly cheaper alternative to Digital Audio Tape-based systems, and far more reliable than analog cart systems.

A Sony Vaio Desktop with a built-in MiniDisc drive. Source: minidisc.org.

Sony did try to further expand MiniDisc’s uses to improve adoption. Limited data storage capabilities were added, and Sony manufactured a line of music-centric desktop PCs which allowed authoring of audio recordings to MiniDiscs. An improved-quality, higher-density version of the format called Hi-MD made its debut in 2004.

Even so, MiniDisc’s days were numbered. Having enjoyed success in these niche markets for a few years, MiniDisc slowly fell to the wayside as by the early 2000s, digital recording evolved into more fluid stateless, file-based systems. The appearance of Flash Memory paved the way for solid state recording of audio and video, and hard-drive based playback devices allowed both consumers and producers to embrace audio file formats such as WAV, MP3 and AAC, playable on multiple devices regardless of the physical storage medium being used.

No doubt, the merging of media recording and playback devices with nearly-ubiquitous smartphones have only hastened MiniDisc’s demise. In an era where music is downloaded, synced, and played back wirelessly via multiple storage devices, or even using intangible forms of storage, the writing is on the wall for most physical containers of digital media, and MiniDisc could be one of many types of this physical media to go obsolete in the near future.