Some of our best digital preservation projects have been the direct result of collaboration; working with dozens of separate entities that all have valuable materials that they want to share with the online world. That collaboration brings some challenges though, and one of biggest problems we’ve run into has been how people name files after they’ve created or digitized them.

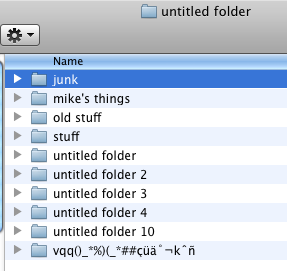

For experienced computer users who store lots of valuable informartion digitally, it goes without saying that clearly naming files is extremely important. Often, the filename is the first thing a user sees that identifies what’s in a file; the information it contains. Without any other cataloging system in place, file names become the way to figure out what’s inside the hundreds of thousands of individual files that can sit on the average persons’ desktop computer, and having countless “untitled” or ambiguously-named files can make finding the information you want nearly impossible.

Fortunately, modern computer operating systems give people a wide latitude in how they can name files. Most people have a file naming method that works best for them, and for the most part, individual systems can work well, so long as they stay consistent and aren’t too hard for most people to easily comprehend. However, things can get a bit more tricky when such files are destined for a digital library, online repository, or other type of internet-based storage and delivery medium. When these types of architectures come into play, some of that wide latitude that modern computers give us in naming files can cause some complications. Web-based content management systems aren’t always as flexible or forgiving with filenames, and can sometimes reject or even mangle files that are more liberally-named.

For this reason, it’s helpful to establish and follow a few simple ground rules when working on a digital preservation project that requires file handling.

In this article, I’ll list some of the basic recommendations that ensure file processing on a digital library project will go smoothly. I’ll also point out some tips and tricks that have worked well for us in projects handled here at the Digital Curation Research Center.

Online File Naming: The Ground Rules

- Keep It Simple

Some of the clearest and best file names avoid complication, and keep things clean and neat. This means sticking to standard alphanumeric characters as much as possible (Upper and Lowercase A-Z as well as numbers 0-9). Filenames such as “EndOfYearReport-2010.doc” and “EdSmithBiography.pdf” can tell you quite a lot about what to expect in the file’s contents, without having to be overly complex or lengthy.

- Avoid Special Characters

Although most desktops are fine with the following characters in file names, most web-based systems are not. For this reason, you should avoid the following characters in your file names:

! # $ % & ‘ ( ) + , .

; = @ [ ] ^ ` { } ~

Additionally, these characters will often cause problems even on some desktop filesystems, and should never be used when naming a file:

” * / : < > ? \ |

- Avoid Using Spaces

Some of the earliest file systems for computers had a strict limitation that prevented the use of spaces. Although current operating systems for desktop computers eliminate this restriction and make it very easy to use them, the use of a space in a file name can still be very tricky for online, web-based repositories. Some may replace the spaces in a file name with special character codes (see illustration to the right and above) that can come up as gibberish when retrieved later. For this reason, spaces should be avoided if you know that the file is going to be uploaded or retrieved from an online system.

Instead of using spaces, consider using hyphens (–) or underscores (_) as separators instead. The use of CamelCase in file names might also be a good way to help you make out individual words.

Tips and Tricks that have worked for us

Having dealt with creating, sorting, transferring and storing literally hundreds of thousands of digital files over the past several years, staff members at the DCRC have come up with a few tricks that help making the handling of multiple files very straightforward. A few of them include:

- Page numbering using leading zeros

Quite a few of our scanned documents consist of multiple pages, and our workflow requires that each page be scanned as an individual TIF file for our preservation copies. These are then put together to form a single PDF or djvu document that can be viewed by our site visitors as a single item.

To keep these individual tiffs in order, and make sure they are all processed together, we typically choose a document name or number that corresponds to any sort of cataloging or accession number that’s already been assigned to the item. Failing that, a relevant, unique but succint description or title will work. We then follow this name with an underscore (_) and a numeric page number.

An important aspect of numbering these pages is the use of leading zeroes (001, 002… 010, 011… 099, 100, 101…). It’s important to make sure you have enough leading zeroes at the start of your file numbering process that you can accommodate all pages. For instance, a 9 page document won’t require any leading zeros at all, while a 300 page document will require that you start with two leading zeroes (001), a 1,000-page document will require three leading zeroes (0001) and so on.

Why add these zeroes? Unfortunately, there are some pieces of software (including some versions of Microsoft Windows and Mac OS X) that will not numerically sort a group of files properly without them. In such cases, page 100 might get sorted in between pages 10 and 11, for example, because the software will strictly assume that anything starting in “10” will come before “11.” To avoid seemingly random pages ending up out of order when processed into the final PDF or other presentation file, using these leading zeroes helps make sure everything stays in the right place throughout the process.

- Handling Dates

For date-specific items, it’s a common habit for curators and catalogers to put the date in the file name. Doing this is fine, but unless you format your date conventions a certain way, a chronological sorting of such filenames is not guaranteed.

First, seriously consider whether putting the date in the file name is necessary at all. All current computer systems automatically add a date stamp to files as they are created. If the item in question is a born digital document (such a digital photo or MS Office Document), then chances are, this date stamp will correlate pretty accurately to when the file was created or last modified.

If it turns out the contents of a file correlate to a different date that’s worth recording, you’ll have the best luck using a numeric date format with the year first, followed by the month and date (YYYY-MM-DD). This will allow you to sort these files in a way that fits naturally with the numeric sorting that computers will perform on filenames.

Changing Trends: The legacy of the three-character file extension

It used to be that a common tenet of file naming best practices was to mind the number of characters you used in the file extension (the last few characters at the end of a file name, separated by a “.” ). The extension is used by older operating systems to identify what type of content a file might have, and which software package was best suited to open it. These extensions have become a quick way for humans to figure out what’s in a file as well: experienced computer users are familiar with the .doc extension referring to a document created in MS Word; a .jpg file is usually an image.

Very old operating systems were limited in how they handled these identifiers, and restricted these extensions to just three alphanumeric characters. And so for the longest time, a common recommendation was to make sure all files had no more than three characters in the extension.

For the most part, this is still a good practice, but isn’t always possible. In particular, new file formats, such as documents made with newer versions of Microsoft Office, have mandatory four-letter file extensions by default (.docx, .xlsx, .pptx, and so on).

Additionally, as computers have grown more sophisticated, they’ve relied less on file extensions to identify file types, and more on embedded metadata in the file itself to figure out how best to treat it. As a result, it’s now possible to make files that carry no file extension at all.

For this reason, as more software packages start taking advantage of modern file systems, the three-character file extension will start to become less important in the near future.

A last resort: Batch renaming to remove bad filenames

Not everyone will consult a file naming document before they start organizing their content, and so you may find (as we have many times) that you end up stuck with hundreds of files created by someone else, with all kinds of special characters that your digital library platform is rejecting. You can’t really blame the people creating these files; the computer certainly allowed the files to be named this way, and in an ideal world, naming systems would be universally easy. Nonetheless, having to go back and manually rename each individual file is tedious, time-consuming work that no one is really eager to tackle.

Fortunately, there are software packages that tackle this very problem, and can make short work out of renaming multiple files to conform to a standard. Using these tools, it’s possible to go through a directory of files, locate spaces and special characters in their filenames, and either remove the characters or replace them with something less exotic.

For Windows, the most commonly available (and free!) program that tackles this issue is the Bulk Rename Utility. For Macs, there’s the free Name Changer application, along with some commercial tools such as NameMangler (Free Trial, then $10), and Renamer4Mac ($25). And for linux desktops, there’s KRename, and the built-in command-line tool, rename (which also exists in command-line form on the Mac).

Over time, it’s hoped that file naming systems on different computer platforms will standardize and converge as they continue to evolve, and perhaps online web-based systems might become more lenient in how files are named. Until that day comes, a lot of time and aggravation can be saved on the part of catalogers and digital curators by heeding a few rules about how files get their names, and keeping things simple and straightforward.